Lately, there has been a rash of interest in term-limits for both appointed and elected officials. The death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg prompted discussions about the wisdom of term-limits for appointed offices. Senator Diane Feinstein’s detachment from the times that we live in led to talk of term-limits for elected officials.

On the surface, term-limits seem like a good idea. We don’t want a person to become ancient in office, the political equivalent of a soiled doily, with decades of accumulated power. Term-limits, we are told, takes care of that by regularly flushing political offices. Out with the old, new people will have new ideas, ideas that reflect present day America. All we have to do is keep picking new product. Who wouldn’t want that?

The problem with surface-level reforms like term-limits is that politics does not happen in a vacuum. Whack the mole of overstayed politicians and a dozen more problem moles appear, many of them rabid. But before I get to the problems that result from term-limits, we must be clear what we are talking about.

Let’s start with democracy. The basic premise of democracy is that people living under a democratic political system choose their own leaders and/or people to represent them in government. No current democracy anywhere is a political or electoral free-for-all. Every democracy has rules. Our democracy’s rule book is the Constitution. The Constitution, and supplementary legislation, instructs us how we do democracy and representation.

Our laws define what positions of state power are elected and appointed, how these positions operate, and who can serve in these positions. We limit who can run for office (as well as who can vote). In the past, the US had race, gender, and income/property requirements. Now the requirements have to do with age and citizenship. In the US, a person must be 35 years-old and born in the US to run for president. To run for the US Senate one must be 30, for the House, 25.

We also have term-limits. The 22nd Amendment to the Constitution, enacted in

1947, limits the president to two terms or eight years (though this can be

extended to 10 if someone takes office to fulfill a dead or deposed president’s

term). The 22nd came about in response to FDR’s three presidential terms and

fear that more than two terms could lead the US down the path of dictatorship.

Of all the arguments for term-limits for elected officials, limits on how long

a president can serve, based on the danger of accumulated power in a democracy

and how much power the president has to begin with, make sense.

Most term-limits in the US are enacted at the state level. California has term-limits for the state legislature, something I will get into later. The argument behind term-limits in legislatures is that they prevent the body from getting calcified. Theoretically, term-limits means new blood, which means new ideas and new relationships. Term-limits are also sold as a way to end “gridlock.” Again, on the surface this seems reasonable, but things get tricky both philosophically and practically when term-limits are closely examined.

Let’s start with the philosophical argument against term-limits in a democracy. If the basic premise of democracy is that we are free to choose who represents us in government, why should we put prescribed limits on that decision? Certainly, we agree that limits based on race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, political belief, class, or whether or not one owns property are wrong. If age restrictions are supposed to guarantee that elected officials possess wisdom and reason, one look at the current president of the United States tells us the age of a leader can be irrelevant to their performance in office.

If we value the principle of democratic free choice, shouldn’t we be able to return the same person to office year after year if we are satisfied with their work? Democratic elections are a referendum on an office holder. Ideally, the people, not some law, determine whether we re-elect a person or toss them aside. Term-limits strip us of the freedom to make that decision. Term-limits stunt democracy.

“But, what about the power of incumbency and the difficulty of new candidates to get elected to office?” While incumbency does make for familiarity, whether that gives the incumbent an edge in a being re-elected is debatable. What happened this year in Iowa’s 4th Congressional District is instructive.

You know of Iowa’s 4th, even if you don’t know it by name. It is a Republican stronghold in the northwest part of the state. During the 2000s, voters elected and reelected Republican Tom Latham to the House for a total of five two-year terms. Latham was mostly invisible outside of his district. However, in 2012, Latham retired and the notorious, white supremacist Steve King was elected. King went on to be re-elected three times. Many assumed that he owned his seat and would have no problem being re-elected to a fifth term. But something happened.

In 2019, King made one racist crack too many. He also failed to condemn white supremacy. Unwilling to hold Trump accountable for his racism, the Republican House caucus tried to save its reputation by targeting Steve King. They stripped him of committee assignments, which made him useless to Iowa’s 4th.

The 4th’s voters were also sick of his act and that it brought disrepute to them and their district, so they backed a guy named Randy Feenstra in the 2020 GOP primary. King, who had no problem in the past fighting off Republican challengers (in 2018, he got 74.8% of the primary vote), was knocked off by Feenstra, who is now facing a hardy challenge from Democrat J.D. Scholten. Incumbency by itself did not help Steve King.

The one solid edge incumbency gives a candidate is in fundraising, and that, too, has changed some. Now and then, a call to a moneyed supporter or special interest from an elected official usually resulted in a contribution. That is especially true of the official has a long relationship with her donors. But get on the wrong side of power and, as we saw in Iowa’s 4th, the money will shift from incumbent to challenger (national Republicans and the RCCC starved King and funded Feenstra).

Digital technology and online fundraising have also helped eliminate an incumbent’s fundraising advantage. Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 run against Ted Cruz and Jamie Harrison’s current battle against Lindsey Graham are perfect examples of how raising money online blunts the advantage of incumbency.

What Iowa’s 4th and the digital shift suggest is that the problem with our democracy is not incumbency by itself, but how money can keep incumbents in office. Fact is, thanks to lack of campaign finance laws, it takes a hell of a lot of money to not only win an election but to stage a credible challenge. The problem of money in electoral politics is not new. It has been talked about almost as long as the United States has existed.

James Madison’s Federalist Paper No. 10 takes on factionalism in government and how to deal with it. While Madison doesn’t riff on money in politics, Libertarian legal scholars cite No. 10 as a warning against campaign finance restrictions. While No 10 is often were the historical discussion on money politics start, the first mention of money’s influence on elections I found was in the 1832 presidential contest. In that race, Andrew Jackson made campaign finance, specifically the Second Bank of the United State’s monetary support for his opponent, an issue. He also used the Bank’s campaign spending as an excuse to crush it (though he hated the thing from its inception, as did his slave-owning supporters).

While the issue of money in politics was wrapped up in the fight over slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction made it a side a side issue. In the late-1800s, that changed. Progressive reformers, fighting the power of the banks and railroads, advocated campaign finance reform. Since then, the debate over money in politics has been a permanent part of our politics. We’ve seen reforms pass and struck down in courts. Many of these court decisions favored money over the people – particularly Buckley v. Valeo (1976), First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (1978), and Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). Whatever side of the issue one is on, no one denies that money does not influence politics.

In 1990, California voters narrowly passed Proposition 140, which limited terms in the Assembly to six years and the State Senate to eight. It was sold as a return to a “citizen legislature†and a reform to deal with money in politics. In actuality, Prop. 140 was a cynical Republican attempt to break Willie Brown’s control over Sacramento. The Democrats survived Prop. 140, though it did take care of the GOP’s Willie Brown problem. It also stripped the legislature of knowledge and expertise, something which made the Big Money problem worse. A 2004 report by the Public Policy Institute of California found that,

[t]he effects on Sacramento’s policy making processes have been more profound. In both houses, committees now screen out fewer bills assigned to them and are more likely to see their work rewritten at later stages. The practice of “hijacking†Assembly billsâ€â€gutting their contents and amending them thoroughly in the Senateâ€â€has increased sharply.

and

In addition to presenting quantitative results, the report points to more general patterns emerging from the authors’ interviews. These patterns suggest that legislators are learning more quickly than their precursors, but that frequent changes in the membership and leadership of legislative committees, especially in the Assembly, diminish their expertise in many important policy areas. Many committees lack the experience to weed out bad bills and to ensure that agencies are acting efficiently and in accordance with legislative intent.

This lack of expertise puts legislators at a disadvantage. They do not serve long enough to learn the system, the issues, or how the issues and the system interact. Elected officials become overly reliant on unelected staff and lobbyist to explain legislation to them (and, in some cases, rely on lobbyists to help write legislation). While the reliance on lobbyists is less problematic when we are talking about those working for the public interest (increased public-school funding, fire protection, flood control, environmental protections, etc.), the same cannot be said for corporate lobbyists, who work only on behalf of the people who pay them.

I don’t know the exact ratio of corporate lobbyists to public interest lobbyists, but I have been told by elected officials and lobbyists that corporate lobbyists outnumber their public interest cohorts six to one. Corporate lobbyists also have a way bigger bank to tap into. So, when something like digital privacy comes before the legislature, the tech lobby dispatches dozens of lobbyists backed by billions of dollars to thwart or water down legislation, while those lobbyists working for the public’s interest number six and have a bank of a couple million dollars.

The legislature’s reliance on corporate lobbyists leads to bad policy and decisions that can have tragic effects for everyday Californians. For instance, money power welded by the real-estate lobby and developers turns sensible measures to control home building in wildfire-prone rural areas near or in forests into a near-impossible political fight. Moneyed-interests make bank extending suburbs into forest lands, only to walk away when the houses they made a killing off of burn. A seasoned legislator on the side of the people knows how to counter money power and prevent or limit such disasters. The newbie does not.

In 2012, Californians partially faced-up to how term-limits damaged democracy. They passed Proposition 28, which reformed term-limits (a legislator can now serve 12-years in office). While Prop. 28 was a step in the right direction, it did not solve the problem of Big Money. Eliminating term-limits would help, as would as other reforms (proportional representation, making the state legislature one body with more representative, decreasing district sizes, etc.).

Unfortunately, because we’ve been taught to despise politicians (and not big business), it is far easier to sell “I’m sick of your face†as a reform than it is to convince people to support mandating “economic impact analyses of legislation, performance-based management and budgeting, or multi-year budgets.†Even progressives shun egghead policy for destructive yet seductive “reforms†like term-limits. Surely, any deep examination of what term-limits lead to sours their desirability, at least as applied to elected officials.

Appointed officials, however, should be subject to term-limits, especially those who are appointed to an office “for life.†By definition, we don’t use democracy to appoint a Supreme Court justice. The president nominates who he wants and the Senate confirms. We can yell and write letters, but have no power to over whether or not a Amy Coney Barrett or a Ruth Bader Ginsberg gets to serve on the court for life. And once that appointed official is there, that is it. We cannot vote a justice out off office, even if they turnout to be destructive, corrupt, unwell, or senile. The appointed official serves at their own pleasure.

Some argue that the lifetime appointment protects the appointee from political or monetary influence. Sure, but putting a term-limit on a judge or appointed political position doesn’t lessen protections. Term-limits or not, the appointees don’t have to raise money to obtain or retain the job. It is illegal for an appointee to bribe their way into office or to accept bribes to decide something a certain way. That is the theory anyway.

In real life, money finds its way into everything. For instance, corporations spend millions on ad campaigns to support a Supreme Court nominee like Barrett or Brett Kavanaugh. That in itself is a good argument in support of term-limits for appointees. Term-limits, especially to “for life†positions, lowers the stakes, which, in turn, lessens the influence of money. A Supreme Court justice limited to a twelve-year term is far less valuable than someone who can serve for forty-years.

Politics often is much simpler than we are led to believe, however, nothing about politics, government, or legislating is simplistic. Because we are a diverse people with so many interlocking interests and problems, simplistic solutions might be quick but they rarely fix anything as advertised. Those with money power not only know this, they know how to engineer and exploit simplistic solutions to benefit themselves. As California’s experiment with term-limits shows, what is sold as a good government solution can easily be turned into something far more destructive and corrupt than the problem it was sold to solve.  ÂÂ

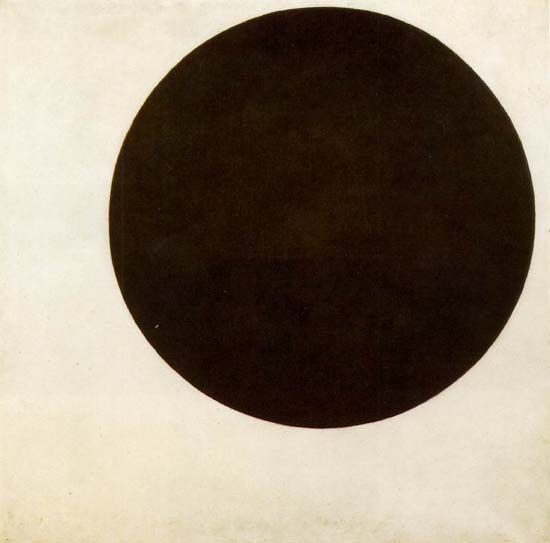

A top: Kazimir Malevich Black Circle (1915)