Monday’s Washington Post ran an article on city politics with the headline “In a setback for Black Lives Matter, mayoral campaigns shift to ‘law and order.’†The story cites mayoral races in Seattle, Miami Beach, and Buffalo where crime has suddenly become an issue (even though, aside from homicide and assault, most crime across the nation has been dropping and continues to drop). The Post report attributes the shift towards “law and order†rhetoric to movement in public attitudes towards crime, as seen in a recent Pew poll, which states that 45% of the public want more spending on police.

To get a sense of what is going on it is important to look closely at and behind the numbers, as well as place the political shift in context. Let’s start with the Pew poll numbers.

The Pew poll has five categories on the public attitude on spending on police. Pew also compare their September 2021 numbers with polling from June 2020. Here are the categories and numbers for the percentage of people “saying spending on police in their area should be…â€Â:

Increased a lot: 21% (2021) / 11% (2020)

Increased a little: 26% (2021) / 20% (2020)

Stay about the same: 37% (2021) / 42% (2020)

Decreased a little: 9% (2021) / 14% (2020)

Decreased a lot: 6% (2021) / 12% (2020)

While Pew uses five categories to measure spending on police, political campaigns will narrow that to two: 1) Those who want an increase or support the status quo and 2) Those who want a decrease in spending. Here is the breakdown for the two categories.

Increase/maintain status quo: 84% (2021) / 73% (2020)

Decrease spending: 15% (2021) / 26% (2020)

The figures above tell us is that at no time have a majority of Americans wanted to decrease police spending. While support of decrease spending dropped nine percentage points between the time the polls were taken, at decrease’s highest level of support (26%), it was still a minority opinion. Additionally, going back to the five categories, the biggest shift in opinion is at the margins, where Increase a lot climbed 10 percentage points from 2020 to 2021 and Decrease a lot lost nine points. The shift in Increase a little, Stay about the same, and Decrease a little saw minor shifts of six points, five points, and five points. That is before we figure in an error rate of up to 2.2 percentage points, which narrows the shift even more.

There is also a problem with Pew’s poll question, something I will examine towards the end of this piece.

Glossed over in the headlines is an important finding: Which demographics experienced a significant and which did not. According to Pew, the biggest shift in Increase, Decrease, and Stay about the same was among White people, those over 50-years old, and Republican/Republican leaning voters. While all demos (White, Black, Hispanic, 18-49, 50+, Rep, Dem) saw a rise in support for Increase, a drop for Decrease, Black, Hispanic, 18-49, and Dem saw their Stay about the same percentages stay about the same. Additionally, in both polls, every demographic favored the Increase/Stay about the same combo over Decrease.

Of course, polls do not happen in a vacuum, nor do public attitudes change on a whim; so, without context that helps explain a shift in opinion, the numbers above are meaningless. The first bit of context: On May 25, 2020, less than a month before Pews’ 2020 poll (June 16 to 22), George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. Before taking the poll, millions of American had seen video of the murder and had participated in anti-police brutality protests. Reporting at the time of these events showed a shift of public attitude towards policing, particularly among White people, those over 50-years old and even a sliver of Republicans. As opinion shifted, qualified support for a decrease in police funding rose.

The shift in attitudes towards police funding happened in tandem with something more significant: According to Gallup, for the first time in nearly two decades, Americans’ confidence in the police dropped to below 50%. At its 2004 high, 64% of Americans had confidence in police – no surprise given the post-9/11 lovefest for NYPD and first responders. In 2019, after more than a decade of high-profile police shootings and murders of unarmed Black people, confidence in police had dropped to 53%. The police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor help drive the percentage down to 48%. When confidence in police fall, thoughts about funding police will change.

The Floyd/Taylor murders and the protest movement that followed did more than shift public attitudes towards the police. Decades of protest over police brutality finally gelled into a substantial anti-racist movement. The mainstream media suddenly became interested in the dirty details of militaristic policing and the nuances of police reform. Celebrities, politicians, and even corporations talked a lot about the police being public servants who are not above the law and some even demanded change.

Longtime advocates of progressive and radical change in policing saw their ideas being talked about and started pushing hard for reform. A handful of lawmakers listened and tried to pass legislation to prevent further police brutality. Even a handful of Republican officials talked the police reform talk. All this occurred while an historically unpopular president was using raw racism to push a “law and order†message.

Something else that is important: We do not have numbers about attitudes towards police funding prior to May 2020. Without those numbers, we have no idea how significant the 2020/2021 shift in public opinion on increasing, decreasing, or maintaining a status quo on police funding is. For argument’s sake, let’s invent some 2019 numbers to compare to 2020 and 2021. The 2019 estimate is based on two things: First, the Gallop poll numbers showing that in 2019 53% of the public had confidence in the police (as opposed to 48% in 2020) and that, in 2019, Black Lives Matter and police reform were outside mainstream discussion. Here are the real 2020/2021 numbers and the 2019 guess:

Increase/maintain status quo: 84% (2021) / 73% (2020) / 90% (2019 est.)

Decrease spending: 15% (2021) / 26% (2020) / 10% (2019 est.)

If the 2019 percentages were true and not an estimate, the 2020/2021 shift would be far less significant than 2019/2020’s. Instead of comparing 2021 to 2020, we’d note that, while support for a decrease in police funding did drop from 2020 to 2021, the 2021 decrease percentage was still 5 points higher than it was in 2019.

Because we don’t have 2019 numbers to compare 2020 and 2021 to, we look for other signs of change. Unfortunately, mainstream pundits tend to ignore what is happening at the grassroots, how energized activists are, and if reform is still being discussed in political circles, and instead focus on “progress,†particular what is happening in legislatures and what rhetoric is being used in political campaigns, measures that misunderstand movement politics and how change happens.

Political change never follows a straight path. It will always be impacted by current events and obstacles beyond the control of those working for change. These challenges create a path that allows two steps forward, one step back, once step forward, one leap to the side, one hurdled barrel, five steps forward, a slam into a wall, a few steps back, etc. In that progression, public attitudes shift, “minor†victories are achieved, and the foundation for further change is solidified.

The 2020 Summer of Floyd/Taylor protests was followed by a few important things. First, a “frank conversation about race†had finally started. Many books were bought and some were read. People started talking and changing. For a nation that has studiously avoided any discussion about race, this was progress. For some White Americans, this was progress enough. Other White folks gained comfort in Derek Chauvin’s conviction. More “bad apples†being charged, fired and disciplined. For many, this was proof that the system was working and that there was no need for “radical†reform such as “defund the police.â€Â

While Black and Brown Americans were pleased some their countrymen were starting to “get it,†most did not share the optimism of their White fellows. They scoffed at the notion that throwing a few bad apples out of a rotten barrel changed anything. They knew that their perception of and experience with policing was/is far different than that of White people, who as a class are much more receptive to the right-wing narrative on crime and policing.

And then there is fear.

In 1973, cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker published a revolutionary book called The Birth and Death of Meaning, in which he tried to bridge the divide between the human mind and body. In his 1971 revision, Becker proposed that:

…human beings, like all living creatures, have a physical body that is born and dies. The fear of death that humans experience, though, lies not so much in the death of the body but in the death of meaning, for it is meaning that defines the human self and society.

In his follow-up, the classic text The Denial of Death, Becker proposed that human’s fear of death was actually terror:

This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression – and with all this yet to die.

As Sam Keen writes in his introduction to Denial…, Becker argued that this terror is so deep and profound that, rather than face it and evolve, humans exile the terror to the subconscious. To keep the terror confined, we built walls inside us. These walls are what Wilhelm Reich calls “character armor,†defenses that keep us from knowing our true self and moving through our current, limited existence.

While our armored walls do an adequate good job of sublimating the terror, our failure to mitigate this intense fear runs up huge costs. One of the costs is anxiety, which feeds off the terror, as well as itself, creating a heighten state of sensitivity, compounding our fears, which can be easily exploited by advertisers, social media companies, politicians, and the like.

Enter modern life and the “existential threats†of war, climate change, and economic collapse, threats that we cannot escape from. Every day, we read and/or watch images of war, wildfires, hurricanes, drought, heatwaves, flooding, resource scarcity, and food shortages. We can rationalize these things by analyzing their causes and calculating solutions, however our conscious deliberation does little to stop the triggering of the primitive fear we feel when viewing frenzied pillars of fire and the bubbled-bellies of starving children, fear that further compounds our subconscious state of terror.

Add to that fear, our daily perception that we live in dangerous society. Mass shootings – though statistically rare – continue to happen, resulting in intense, heavy news coverage. No matter what one’s politics are or how one feels about guns, these shootings, especially when they seem to be random, are very frightening and affect everyone’s sense of security. Further, the right-wing response to these shooting – to meet gun violence with more guns – is also frightening. We are tempted into a permanent state of alert, forever in fight or flight.

Fear is also driven by other factors that have little to do with commonplace violence. The political right not only plays fear-monger but they increase fear by using violent, authoritarian rhetoric. Every Fox-fueled conspiracy theory and video of maskless morons screaming “NO COMPLY†and “I KNOW WHERE YOU LIVE†at school administrators strengthens fear’s foundation. Every video of an unhinged yahoo screaming at fast food cashiers for asking them to wear a mask resurrects memories of Trump supporters battering police officers during the January 6 Insurrection. We fear for our country, our democracy, and our future.

Even what has become routine and mundane adds to the terror. Walk down the street and every masked face is a reminder that death threatens invisibly. The tent in the sidewalk, the plywood shantytown that we pass driving home from work inform us that we are a paycheck, mental breakdown, or medical emergency from living on the street.

All of these fears are compounded by the knowledge that every material problem that I recited has a number of simple, doable solutions and that what prevents us from seriously working on these challenges as a society is the lack of political will fueled by the stubbornness of a small group of bigots, an even smaller group of very wealthy people, and popular mass cynicism.

Stuck, we realize that we “…have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression – and with all this yet to die†(Becker). We see life as meaningless and absurd, which makes us feel alone, thus contributing to the terror.

Enter political reality: Almost all political campaigns are about fear. Democrats run on fear of Trump, of climate change, and of fascism. Republicans run on fear of Democrats, of Black & Brown people, and of buggery. Everyone runs on the fear of economic collapse. We’ve had fear campaigns since this country was founded. We will have them until it finally collapses. No vote for anyone will stop the fear or fix what causes the fear, either in the material world or our subconscious.

Another political reality: All political campaigns are about “law & order.†No politician runs on “crime & chaos,†and that includes politicians like Donald Trump who thrive on both. Reactionary, conservative, moderate, or progressive, all politicians preach law & order, albeit with different interpretation of what that means.

We are very well acquainted with the right-wing version of “law & order†– lock ‘em up and shoot ‘em in the streets – but how about the left’s vision of “law & order,†say that of Black Lives Matter (BLM)?

Without using the phrase “law & order,†BLM’s law & order campaign is for police to obey the law and for their law-breaking to be met with the same seriousness and severity that civilians face. It is for an order in which there is no “thin blue line†between police and the public and that all people are treated with the same level of respect and dignity, regardless of race, ethnicity, skin color, gender, sexuality, or anything else that defines their individuality. It is also for an order that has a minimal role for police, who are to be used primarily as mediators. When police are needed to deal with danger, when armed, they should not be seen as first responders but the last resort. Finally, police should have little to no involvement in social issues like homelessness or public health crises like mental illness.

That last point about social issues and public health is the essence of the demand to “Defund the Police.†Curiously, it was not addressed in the Pew poll cited at the top of this piece. In the poll Pew asked: “Thinking about police departments in your area, do you think that spending on policing

should be… â€Â, followed by Increased a lot, Increase a little, Stay about the same, Decrease a little, and Decreased a lot.

Nowhere in the poll was anything about decreasing police funding and diverting that money to increased spending on first responders who deal exclusively with homelessness, addiction, and mental illness. While very few people want a blanket decrease in police spending, according to one poll, 72% of Americans support “reallocating some police funding to help mental health experts, rather than armed officers, respond to mental health emergencies.â€Â

These percentages – those indicating support for “law & order†or desire to shift some resources from policing to social services – will shift over time. They will be influenced by recent events and how much fear the public feels. And, with these shifts, we will read pundits’ muddy proclamations that police reform is dead.

Absent in these funeral notices is the reality that political and social movements take time to grow, mature, and make gains. Policy shifts and even what politicians run on are the end result of years of organizing and should never be undervalued or used as a measure of the health of a movement. This is especially true with the police reform/defunding movement, which has spent over five decades exiled to the margins by powerful police unions, conservative and centrist politicians, private prison companies, and a whole host of other interests who benefit from the right-wing version of law & order. Given these obstacles, that we are having debates over things like reallocation of police resources and eliminating qualified immunity is near revolutionary.

Beware mainstream proclamations that movements for change are dead. Be critical of polls that simplify issues with questions that elicit answers of more, less, and same. Know that no matter how politically astute you are, your subconscious is full of primitive fear that others will try to exploit. And believe that all change takes hard work and time, that progress never walks a simple, forward path, and that seemingly small victories, such as pushing the conversation into the mainstream, are really quite profound. ÂÂ

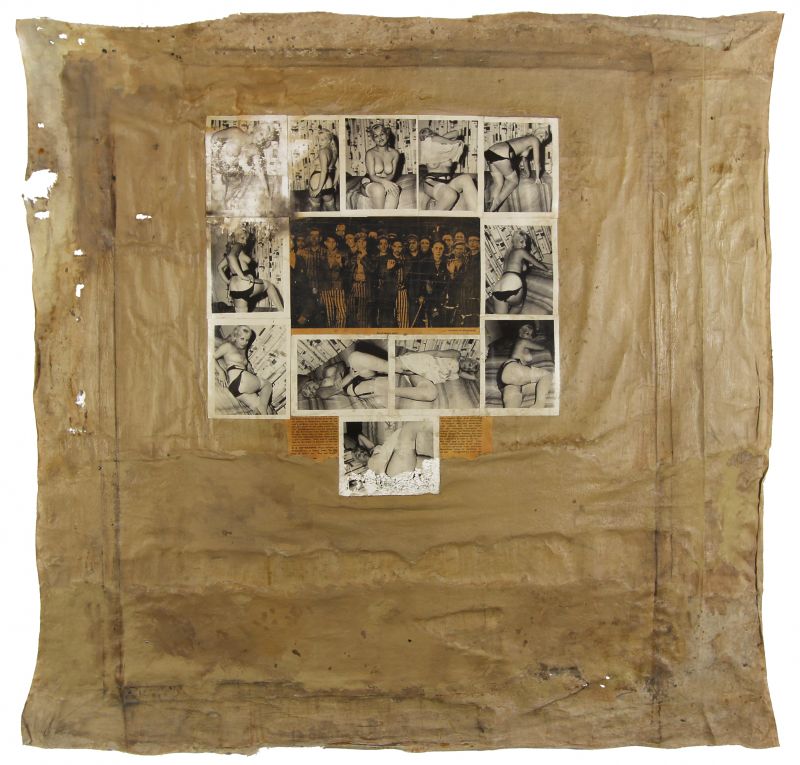

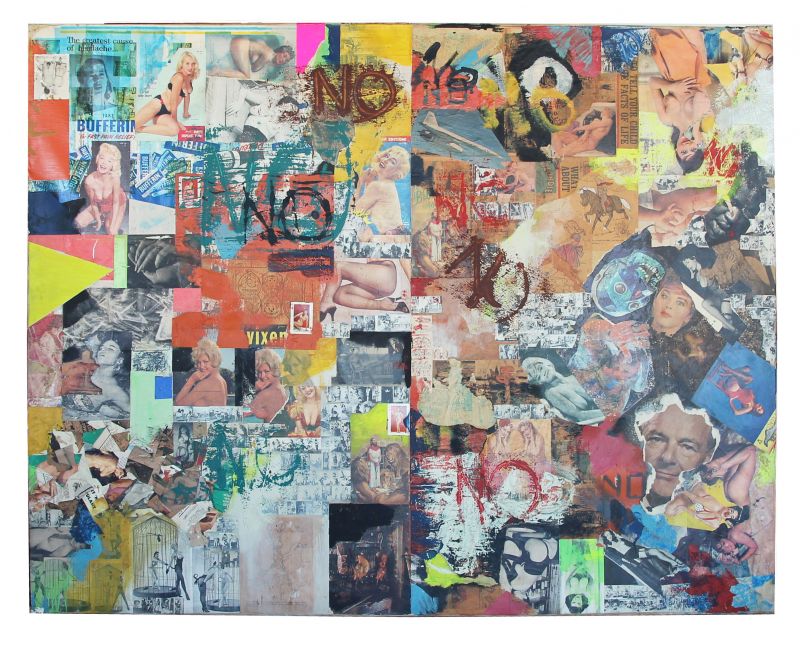

Atop: Boris Lurie Saturation Painting (Buchenwald) (1960-1963)