Recent events, particularly those in Texas, have brought the filibuster fight to the fore. So much so that a friend recently asked me, “What’s the downside to killing the filibuster?â€Â

I thought about it for a while and one thing I kept coming back to is that Americans might be familiar with the word filibuster and the general concept, but there is so much mythology around the filibuster that we get lost in debates that have more to do with political fantasy than reality. The best way to get to reality is through a bit of history and analysis.

When the Framers wrote the Constitution, one of the central topics was how the legislature would decide things. Because they were dedicated to bringing about a democracy, they knew that votes within both legislative chambers – the Senate and the House of Representatives – would be the main decision-making tool. The next question was how to tally the votes.

The Framers had three options: Consensus, where there is unanimity in agreement; a super-majority, where a two-thirds vote is needed to pass legislation; or a simple majority of 51%. They believed that consensus was unrealistic. Their experience with the Articles of Confederation informed them that a super-majority was unworkable. So, they went with a simple majority. In order to pass legislation, each chamber needed at least 51% affirmative votes.

The Framers left it up to each chamber to determine how they structured their inner-workings to conform to the Constitution. Since this piece is about the Senate filibuster, I am going to stick with the Senate.

The first Senate convened in 1789. It started by structuring how the Senate would run (the “Senate rulesâ€Â), including how debate on legislation would happen. On ending debate, they didn’t have a plan. An idealistic bunch, they figured debate would end when the senators were ready to vote. But people being people, some senators figured that if they drew out debate, they could get their way on things. That is what happened on the first day:

The tactic of using long speeches to delay action on legislation appeared in the very first session of the Senate. On September 22, 1789, Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay wrote in his diary that the “design of the Virginians . . . was to talk away the time, so that we could not get the bill passed.

No way the other senators were going to let the Virginians ride roughshod over the Senate. They decided to end the as-not-yet-named filibuster before it became a problem. Martin B. Gold writes, “The original Senate Rulesâ€â€then only twenty in numberâ€â€allowed a Senator to make a motion ‘for the previous question.’ This motion permitted a simple majority of Senators to halt debate on a pending issue.â€Â

Vice President Aaron Burr was against the previous question rule. He argued that because all votes were decided by a simple majority, the rule was redundant. If the senate wanted to vote, they could vote without having to vote to end debate (people on both sides on the filibuster debate have argued that Burr is correct). While Burr didn’t win that immediate fight, the Senate functioned well enough that in 1806, the Senate did away with the previous question rule. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, they didn’t create something to replace it.

In the years to follow, a few senators did take advantage of the absence of an end-of-debate rule; however, not often enough for it to be considered a problem. While there were great tensions between the North and South over slavery, tariffs, and trade, an even stronger desire to preserve the union forced opposing parties to work out compromises, not always in the best interest of the people.

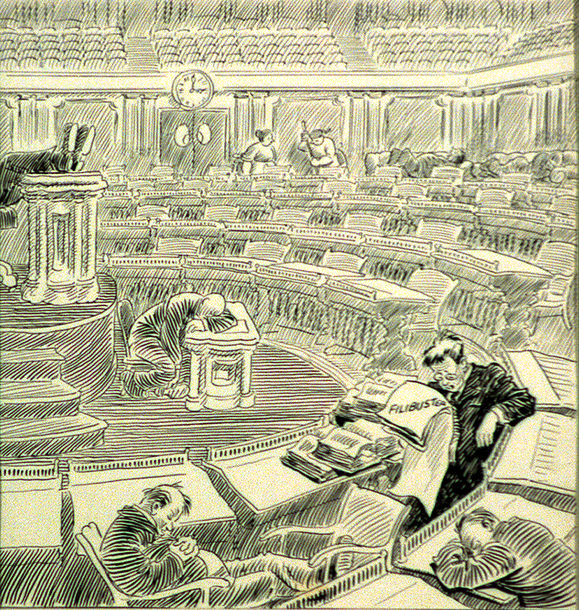

Of course, that cold peace would not last. The Senate historian writes, “While there were relatively few examples of the practice before the 1830s, the strategy of ‘talking a bill to death’ was common enough by mid-century to gain a colorful labelâ€â€the filibuster.â€Â

The first officially recognized filibuster occurred in 1837, when opponents of President Andrew Jackson used it to prevent Jackson allies from tossing out a censure that the Senate had imposed on the president. Though Jackson’s enemies’ tactic was successful, most senators considered the filibuster a mere nuisance, that is until 1841:

In 1841 the Democratic minority attempted to run out the clock on a bill to establish a national bank. Frustrated, Whig senator Henry Clay threatened to change Senate rules to limit debate. Clay’s proposal prompted others to warn of even longer filibusters to prevent any change to the rules. “I tell the Senator,†proclaimed a defiant William King of Alabama, “he may make his arrangements at his boarding house for the [entire] winter.â€Â

King’s warning went unacted upon. The Senate historian writes “[w]hile some senators found filibusters to be objectionable, others exalted the right of unlimited debate as a key tradition of the Senate, vital to tempering the power of political majorities.†The unregulated filibuster was to continue for another 76-years.

In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson, trying to knock back Senate opposition to US involvement in World War I, lobbied the Senate to do something to end the filibuster. He argued that the Senate was too big and the country’s problems too complex to allow a few senators the power to stop all business by refusing to end debate. A majority of the Senate agreed. They “adopted a rule (Senate Rule 22) that allowed the Senate to invoke cloture and limit debate with a two-thirds majority vote.â€Â

Senate Rule 22 has had a few tweaks – most notably Mitch McConnell allowing debate on judicial nominees to end on a simple majority vote – but no reform serious enough to stop the tactic’s use. And, while there have been major filibusters – such as those held in the 1950s and 1960s by Southern conservative to hold up Civil Rights legislation – until the 2000s, the Senate filibuster was held in check by two things that Americans tend to loath: Political horse-trading and power politics.

As far as their fellow senators were concerned, if you use the filibuster, it best be for a good reason. Play fancy with it and the votes and favors you exchange with other senators, vital for passing your pet legislation, disappear. Your popularity among your colleagues and constituents fades and your power goes bye-bye.

If being sent to the unpopular table doesn’t work, a strong Congressional leader, like Lyndon Johnson, will be happy to crush your balls. That’s power politics.

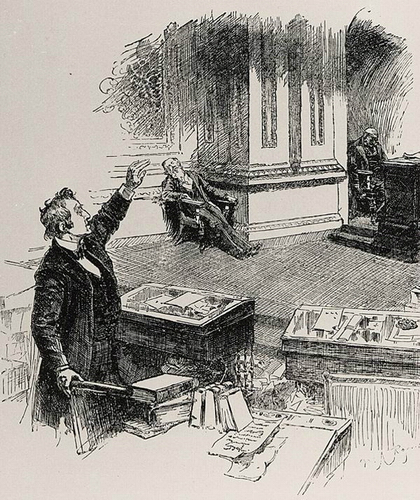

All this meant that when the filibuster was used it was used as a tactic of last resort and as such a mythology formed around it’s use. The myth informed us that the filibusterer was a hero of sorts (see Mr Smith Goes to Washington), a lone fighter for what he believed was right. No matter that what he believed was quixotic, stupid, or racist, the point was that here was a single man daring to say “No!†That is not to say, people fighting the good fight didn’t use the filibuster to stop bad things, they did. And, their use of it, helped build the mythology.

Remember the filibuster is a tactic. A tactic is not a strategy. A tactic is a tool that is employed to advance a strategy. While the filibuster was initially used to kill legislation, as a tactic it was also used to change legislation. Filibuster or threaten to filibuster and a senator might be able to get this put in or that dropped from a bill. The use of the filibuster as a tactic to change legislation helped create the myth of the filibuster being a “tool of compromise.”

Like a lot of myths, there is some truth to the compromise myth, but that myth is not The Truth. If there is The Truth, The Truth is what is always was, the filibuster is a tactic one uses to get one’s way. That is not what supporters of the filibuster want the public to hear. They want us to believe that filibuster = compromise, which is bullshit.

Stinkier than bullshit is that the idea that filibuster = compromise assumes that the filibuster creates compromise. In this reading, the filibuster is holding a knife to the rope keeping a giant piano from dropping on the Senate if the refuse to compromise. That is not true.

While there are outside forces that move parties to compromise, compromise does not happen unless both parties are willing to compromise to begin with. Without the willingness of all sides to compromise, politics become an alternating series of death matches and capitulations.

Starting in the 1990s, House Republicans under Newt Gingrich refused to compromise with Democrats. Because they were successful enough in getting frightened Democrats to capitulate, the Senate, particularly Mitch McConnell, took notice.

In 2008, when executive power changed from Republican to Democratic, McConnell started his reign of obstruction. Overtly, McConnell sold his No Compromise strategy as necessary to prevent Democratic “overreach†and the “threat of socialism.†Covertly, he used racism to justify his fight against the First Black President. Either way, McConnell strategy and main tactic to thwart Democrats was No Compromise.

The minute McConnell committed himself to No Compromise, the myth of the filibuster as a tool of compromise died. Those who continue to push the filibuster = compromise line are either stuck in a historical la-la-land or are arguing in bad faith. That hasn’t stopped conservative Democrats like Senator Joe Manchin and Senator Kyrsten Sinema, centrist pundits, and Mitch McConnell from arguing the compromise point. Nor has it stopped the press from uncritically repeating this fallacy. But, know that all you have to do is look at McConnell’s reign as Republican Senate leader to know that compromise is dead.

There is a darker view of what will happen if the filibuster is dumped. Some warn that if the Democrats get rid of the filibuster, the Republicans, if they take back the Senate, will abuse it’s absence. Without this “restraint,†they will hammer through all kinds of destructive and anti-democratic legislation. On the surface, that prediction is sound, but it is just one prediction.

I also have a prediction, one based on recent history, a prediction that is as sound as it is grounded in reality: If the Democrats keep the filibuster, the minute the Republicans take power, they will do away with it, just as they did away with the filibuster for judicial nominees. They won’t ask permission from the Democrats. They won’t carry on in the press about Senate tradition and unifying the country. They will take their simple majority and change the rules to close debate with a 50+ votes.

And when the Republicans get rid of the filibuster, they will blame the death of “this fine Senate tradition†on the Democrats. They will tell us that the Democrats’ “stridency†and “unwillingness to compromise” forced their vote. They justify the loss of the filibuster as necessary to “defeat socialism” and yabba dabba doo.

Doubt this and you haven’t been paying attention. We are talking about a political party who still says that the 2020 election was rigged, that the Jan. 6 insurgents were tourists, who deny COVID, who just let loose misogynistic vigilantes in Texas, who routinely use lying and misinformation as political tactics, who know nothing but blood-sport politics, and who very much would like to turn this country in to an authoritarian regime on the level of Hungary or Turkey.

The only things that Republican leadership holds sacred are power and money. They have proved that they are willing to do away with democracy to preserve their power. Why would they hold onto a “Senate tradition†that was born of a loophole, that has done as much – if not more – bad than good, and that prevents those in power from actually ruling?

So, is there a downside to killing the filibuster? Maybe in Mommy Daddy Little Foo Foo Land, but in the United States 2021? Please.