Have you ever thought about what you want the world to be like for you and your family? I am not talking about three-hots-and-a-cot or the basic minimum for survival but what you really want. Have you ever crafted your utopia?

I ask because knowing your utopia is a powerful thing. A utopia is target beyond “back to normal†or “enough to get by.†Push for “normal†and “enough†and we get less than we need. Visualize and fight for utopia and that gets us closer to a better world. And, when that fight is not wrapped up in idealism, striving for utopia is good for our psyches and our souls. I’ll tell you about my utopia.

My perfect world is one in which toil is greatly reduced to what is absolutely necessary. It is a world where consumption and production are limited to quality things, useful stuff that are well crafted and purposeful, utilitarian and ornamental. We make what we need and want, not what we are expected to sell. We do not produce waste and we reuse and repurpose things that are longer needed.

In my utopia, there is enough good food for everyone. What we eat is healthy and satisfying. Our pallets are so pleased that we don’t desire cheap taste. Cherries taste like cherries, chocolate like chocolate, and we all get a piece of the pie.

In my world, Earth is treated as “a common treasury.†We don’t soil or spoil it, for it belongs to all of ours. No one person has claim to any resource other than their own labor. The wealth we create is distributed equitably, not via stock schemes, exploitation, or inheritance. Physical labor is valued at the same level as mental or creative work. Scheming and trickery are not rewarded.

Of course, we play! We play a lot, but we also work. Our work is meaningful and personally fulfilling. Right now, most of us work useless jobs – pushing paper for insurance companies, selling plastic doodads and thingamajigs, helping others make money from money. We spend at least one-third of our time at work, one-third at sleep, and one-third on our personal life – raising our family, doing good works, running errands, educating ourselves, being creative, engaging in recreation, doing physical and mental maintenance on ourselves, finding stimulation, and “nothing.â€Â

In my perfect world, we spend no more than 20-hours a week doing necessary work. Gone are jobs that are there only to provide employment or generate wealth. My utopia has no insurance salesmen or stock brokers. No one is employed making plastic things to put in Happy Meals. Because the bullshit jobs are gone, there is a surplus of labor. Not enough work for people to do…unless the work is distributed evenly. We all work less.

While people work jobs that interest them and of which they are best suited, they do not do the same thing month after month. Here’s my “work scheduleâ€Â: Springtime, I am part of a team that works at a farm, sowing the soil and preparing for the growing season. Come summer, I engage in maintenance of the infrastructure – buildings, parks, the energy grid, a small fleet of shared vehicles, etc. Winter, I am part of a group of teachers, educating children, adults, or both.

Fall, what about the fall? Great band, also my time to do what I want, something that fulfills my needs and contributes to the commonwealth. Maybe I research, write articles and books, or play music. I want to help heal so I train to be a doctor or therapist, and do that in the season I get to call my own. Or, I really like working on a farm, so I go back and help with the harvest. The point is that I am engaged in my society at different levels, doing different things, things that not only matter to me and contribute to the greater good, but stuff that tells me that I have a stake in society, that the work I do is important to keep this utopia going.

And, because this is my world, all this seasonal work is limited to 20-hours a week. That gives us at least 20 more hours than we have now to do what we want to do – which can be anything from fixing things for our neighbors (because I enjoy busy work and helping people), writing stories, going on long hikes, or staring at the ocean, doing “absolutely nothing.†Vacations? Of course! Retirement? Certainly, but if work isn’t toil, tending gardens, teaching kids, telling stories, and healing the sick can done til one’s final days.

Capitalists worry that without the profit motive nothing will get done, that we need that monetary reward to fuel production. My counter is that we need to rethink “profit.†Traditionally “profit†is “financial gain.†How about we measure profit in time, fun, fulfillment, friendship, meaningfulness, and a sense of community. Or forget profit. Emphasize the value of things I listed and they become as powerful of a motivator as money, especially when want of wealth is devalued and basic needs are taken care of.

Revaluing what we do and why we do it isn’t some farfetched theory based on some pie-in-the-sky notion of perfection. Chances are, right now, you are at home reading this. You are not working or your work load has shrunk. While you are dealing with stress and boredom, you are also discovering that there is a whole lot of things in your life that you do not need, things you thought were necessary but are not.

After the initial shock of being sequestered, you find that you dig all this family time. You learn or relearn how to communicate with others. You call people on the phone whom you haven’t spoken to in years and you wonder why it took so long. You write letter-length emails and texts to people. You create stories, songs, or poems. You paint things – a landscape or your bathroom.

You think about what you are going to do next. You reevaluate what you do every day, what you do for a living, and how much time you spend at work. You worry about money but you now wonder if there is way to get what you need outside the rat race. You know that there should be more options, with all the wealth trapped at the top, there has to be. You want things to change. Your world has opened up and you are starting to see possibilities. Now start thinking about your utopia.

My utopia is a bit quieter than the everyday world I am used to. It is much more like the streets of San Francisco are today, under this shelter-in-place order. Of course, I’d like to see more people out and about, but I am perfectly fine with the lack of cars. My utopia’s clean air and clear water isn’t a fantasy. Lockdowns in China and Italy (and I assume elsewhere) have led to a drop in emissions and better water quality. In my utopia, people reach out to their neighbors and comfort their friends, as they are doing now. They pay attention to what is happening in their community, as they are doing now. They care for each other, as they are doing now.

“But, what if people want to be lazy?†My answer is: What if there is a drought? What if it rains for forty days and forty nights? What if a meteor takes out New Mexico? The answer to “What if?†is that we plan for what we can and we deal with what happens when it happens. Criticize me for being unrealistic, say that I am not “practical.†Fine. You miss the point. I am talking about my utopia, not my reality or even what I expect the world to be like when we start working on my utopia. I am talking about my vision for the future.

In the real world, the only thing that makes my utopia impractical is that my vision does not take into account your vision. My utopia and your utopia will come in conflict, and that is fine. We can still work for something better and if, we get to the edge of utopia, we’ll start wheeling and dealing. You want little shops everywhere; I say okay if we make sure no one is getting exploited and that they don’t sell garbage. You want to have some form of exchange; I say okay if there is no gross accumulation of wealth. We find middle ground to get to a better place.

I am confident that a fulfilling life, meaningful work, more leisure, and a lack of want will mean less crime and violence, less depression and despair. A more compassionate society will also mean that we put more emphasis on cooperation than competition, live becomes more than making money.

The space between utopia and the society that we have today contains plenty of reality. We move one quarter of the way towards utopia and we are in a better place. By envisioning our personal utopias, we make ourselves authors of the future. We go from spectator to participant.

With a utopian vision, we stop looking at society through the lens of super hero movies. We reject the notion that the default world is an evil place and that only an elite group of warriors keep the worst from happening. Know that none of us are props or pawns without a say in what is going on and no agency in life.

A utopian vision helps break our addiction to dystopian culture and the feeling of helplessness if fosters. Westworld, Handmaid’s Tale, Blade Runner, The Walking Dead, Man in a High Castle, The Purge, Hunger Games, Years and Years, Fury Road, Black Mirror, The Matrix, even the Star Wars franchise – Our senses are bombarded with visions of the worst of all possible worlds. While these series and films are also hero/villain tales, the society the stories live in are so sinister and oppressive that mere survival is framed as winning. Of course, life is more than survival and our literature contains more than dystopia.

Although utopian literature dates back to Ancient Greece and China, the word utopia was coined by Thomas More and used as the title of his 1516 book, Utopia. More’s masterwork inspired 16th and 17th Century writers to create their own visions of society. Sir Francis Bacon wrote New Atlantis (1627). Margaret Cavendish wrote one of the first fusions of science fiction and utopia with The Blazing World (1666). Gerrard Winstanley, Digger and anarchist, wrote The Law of Freedom in a Platform (1652), a tract that influenced my utopia. The 18th Century is a bit thin on utopian literature but Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is worth noting as a satirical take on both utopian and dystopian society.

Inspired by socialism, the farmer’s movement, and a growing labor movement (which were in turn inspired by utopianists), the 19th Century saw a flood of utopian literature. The three most famous (now forgotten) are Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), William Morris’ News from Nowhere (1892), and Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872), a piss-take on the idea of utopia (Erewhon is the backward spelling of nowhere).

The early 20th Century saw a few utopian titles but World War I and World War II, and the rise of authoritarianism between the wars, turned literature towards dystopia. Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin kicked things off in 1921 with his novel We. Two heavy hitters followed: Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and, the big daddy of them all, George Orwell’s 1984 (1949). Huxley and Orwell’s dystopian visions established a genre of over a thousand fictional dystopias (especially in science fiction). Brave New World, 1984, Handmaid’s Tale, and text of a similar tenor such as Lord of the Flies and Animal Far are taught in high school, as cautionary tales. Dystopia is part of our curriculum. Utopia is not.

Although dystopia dominates culture, utopian literature didn’t go away. Each decade of the late 20th Century contains at least one utopian classic: Austin Tappan Wright’s forgotten novel Islandia (1942) and Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End (1954). Aldous Huxley attempted to balance his dystopia with Island (1962). Inspired by the environmental movement, Ernest Callenbach wrote Ectopia (1975). Ursula K. Le Guin and Kim Stanley Robinson round out the century with two classics, Always Coming Home (1985) and Pacific Edge (1990). Utopia is alive if you know where to look.

Modern utopian visions are not only crucial if we want change, they are necessary for our psychological and spiritual well-being. Utopias balance our fat diet of doom. Utopias open our eyes to something better. Utopias suggest possibilities, possibilities that are better than what we have. Utopias help us create roadmaps for the future. Utopias remind us that we have a lot of good within and around us. Utopias give us hope. With hope comes action, with action comes positive change, and with positive change comes a better, kinder, fairer, and more compassionate future, one step closer to my utopia and yours.

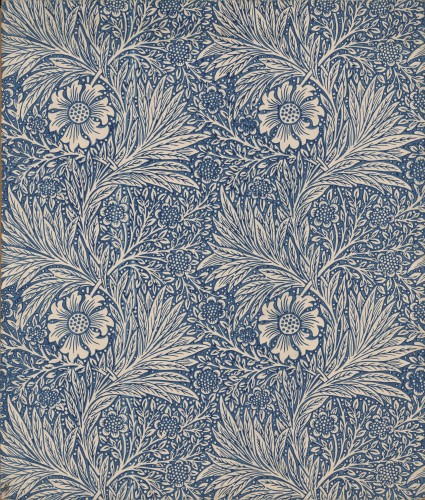

At top: William Morris Strawberry Thief (1983)