Before the internet, cell phones, and instant communication, news was reported and consumed like this: An event happened. Planned or spontaneous, the reporters on the scene reported what was happening in real-time.

Of the three mediums – print, television, radio – radio was usually the first to report an event in real-time. The reason for this is because for a radio reporter on the ground to get the word out as an event was happening. all that they needed was access to a phone. Even a landline meant direct contact with the radio station. It was also easier to “break in†the middle of a broadcast on radio than the other two mediums. Programing – especially music – wasn’t as fixed as TV. Advertisements could be juggled. Because there were plenty of radio stations, there were stations dedicated to news – something that didn’t happen with TV until the rise of cable.

Early television’s ability to break news in real-time was limited by technology and expense. Because TV reporters dealt in images, they could not relay visual information over the phone. Commercial satellite technology changed that, but, just for a few. At first, only the major networks, followed by big-market stations in major cities, could afford the gear needed to report visuals in real-time. Also, programing, including the airing of advertisements, was fixed to a tight schedule. Only something like the death of a president or man walking on the moon warranted a news break. Everything else would have to wait until the 6 o’clock news, later joined by the morning news, the late-night news, the afternoon news, the midday news, and, eventually the 24/7 cable news – a progression that took decades to happen.

The physics of print explain the difficulty of reporting news in real-time. When an event happens, the facts must be reported, written, edited, set to type, laid out, copy-edited, and printed. If something of monumental importance happened – the assassination of a president, an attack on the country, etc. – there would be a Stop the Presses moment, something that happened far more often in the movies than in real life, and which still required a lag in time from reporting to public consumption. Thus, newspapers served as a daily digest of events, reporting the day’s happenings, either in the evening, the next morning, or both if your town was fortunately enough to have two papers.

Magazines and Sunday newspapers were unable to report news in real-time or even same-day, so their editors did what those print mediums could do best: Provide in-depth news coverage in an expanded digest format, with commentary and analysis. This practice was especially true with monthly magazines, but also with weekly and bi-weekly reads, as well as the Sunday edition of the newspaper.

When weekly English-language newspapers hit the scene, they augmented an alternative perspective on the news with long-form journalism.  Reporters for weeklies had days, instead of hours, to flush out a story. TV and radio also adopted to long-form magazine-style journalism and analysis, as seen on weekly television news shows like 60 Minutes and programs of analysis such as Meet the Press.

In 1975, PBS launched The Robert MacNeil Report (later MacNeil/Lehrer Report and PBS NewsHour), a daily news show that focused on fewer stories but deeper reporting coupled with explanation and analysis. National Public Radio, as well as community radio stations, particularly the Pacifica network, put a similar twist on news reporting.

No matter how the news was reported, regardless of the medium, those who reported the news and the people who consumed it understood the strengths and limitations of the different mediums. This understanding informed the idea that real-time reporting would always be incomplete, that new information would come as events unfolded, and everyone should refrain from or be very wary of real-time analysis. True knowledge of the how’s and why’s, and even what’s and who’s, would and could not be known until investigations uncovered enough information to allow careful and comprehensive analysis to be done. Such an endeavor took time. Haste borne by impatience would most likely lead to incomplete or incorrect conclusions, which could result in faulty solutions and destroyed lives.

In 1980, Ted Turner created the Cable News Network, commonly known as CNN. It was cable television’s first successful foray into a news-dominant network. Two years later, Turner launched CNN2, which reported news 24-hours a day, 7-days a week, in 30-minute news segments. With CNN2, the 24-hour news cycle was born.

Problem with a 24-hour news cycle is that there is only so much news one can report on in a day, at least, news which will hold the interest of viewers. Natural disasters are great TV. One major hurricane, wildfire or earthquake can take up more than 50% of a day’s news coverage. Throw in weather, sports, and whatever the stock market is doing, and, of the 24-hours, the 24/7 news network is left with no more than 6-hours for reporting on politics, foreign policy, war, crime, and personal-interest stories.

Six hours of news-news broken up over 24-hours means that a 30-minute segment would provide a viewer with 8-minutes of news-news, less when you account for time dedicated to advertisement, show introductions, and “witty banter†between the anchor and the person doing the weather.

Eight-minutes or less of news-news in a 30-mniute segment is not a major departure from standard network or local television news. However, if there is no disaster, war, or scandal eating up news time, then what? CNN answered by looking to sports broadcasting, where play-by-play announcers were coupled with color commentators, and, later, sideline reporters. CNN brought on a series of experts to explain the news and analysts to “get behind the story.â€Â

When CNN’s color people were tapped to explain or comment on real-time news coverage often the results were absurd. An on-scene reporter would relay, “The rain is falling hard, so hard that the town is flooding.†The show’s host would restate what the reporter just reported and then turn to an expert who would tell us that rain is, indeed, water that falls from the sky and an analyst would add that when rain fell at a rate and volume that was too much for the ground to absorb, we would have flooding.

Later on, CNN would assemble panels of experts and analysts who each gave their individual take of the same event, often differing only in their wording and tone, which, objected to, would lead to a round of yelling, which was framed as “debate.†Cable news networks like MSNBC and FOX News refined CNN’s breakthroughs.

Watching this mess, the viewer was left with nothing they wouldn’t have known by just listening to the on-the-scene reporter, except the idea that they needed to know everything about everything right now. The practice of getting the basic facts from real-time reporting, paying attention for revisions and deeper reporting, and waiting, even a day, for the information to marinate enough to be analyzed and understood had been breached. The next development in news deliver would have a profound and damaging impact on news consumption.

The early internet was a slow, clunky pain-in-the-ass which was only good for a limited number of things, mostly compiling information with a quirky, zine-like obsession and communicating with others in text. Because images could take minutes to “load†and video much, much longer, even real-time reporting in text was limited to the basic information.

When someone famous was shot, the internet user got the information fast, but any video or audio – images of the shooting, a stock photo of the victim, a recording of sirens – was slow to come. Updates would come in bits and, perhaps at the day’s end or the next, someone like me would blog about what happened and give their opinion and analysis.

Technological advances allowed information to be transmitted much faster than before. Amateur news-gatherers, bloggers, and tech-savvy reporters were able to scoop all traditional media by reporting in real-time but without restrictions – mostly editorial, often ethical – that slowed established outlets.

News consumers, looking for instant information and real-time analysis, gravitated towards the web, particularly new media sites. Seeing circulation drop, print media, particularly newspapers, who were already struggling with the 24-hour news cycle, started investing heavily in online news operations.

While a few “old media†operations succeeded online, many were hamstrung by adhering to traditional news reporting, as well as a financial structure that they were not set up for. Consumers, now staring at a screen at leisure and for work, expected information and analysis to be delivered in real-time, just like it happened on TV. New online media saw a market there and filled it with clickbait sites, semi-clickbait sites (like BuzzFeed), and sites like Politico that combined news and analysis.

Along came social media, which did not create the desire for instant understanding, but certainly reinforced our want for it. Social media also invited people with little or no grounding in journalism, analysis, history, or much of anything else to act as commentators and analysts. Instantly, everyone with access to a phone, the day’s news, Wikipedia, and Google became a “content creator†and were treated as experts, most often by readers. Not wedded to things like standard journalistic practices or ethics, the new “experts†gave questionable takes on events as they unfolded in real-time. With those takes came demands for certainty and unassailable answers.

The new “experts†and social media pundits made and make a lot of mistakes in their analysis and “reporting†which often was the sharing of news stories); however, their biggest contribution to our current problems with news consumption is the idea that, to be informed and to be a good citizen, we must know and understand everything about a day’s events right now as things are happening and have an opinion on those things right now. Not knowing is not an option here. We must know what happened, why it happened, who was impacted, who is responsible, and what that means for the future right now even if we have incomplete information and no time to responsibly analyze that information.

Thus: We demand to know why public officials do not have a solution to a problem right now and why things are “taking too long.†We have ideas of how things are supposed to work and express them without stopping to measure what we know against procedure or history or science. When the official explanation fails to meet our expectations, we start making assumptions. We project what we think is happening onto the actions of others without knowing why someone is or is not doing something a particular way and at a particular pace. We fall prey to misinformation and disinformation campaigns designed to fill the gaps of what we don’t know. We drift into conspiratorial thinking, hoping to find an explanation for all of our questions. We seek total knowing in a world where even knowing most of what is going on and why is impossible. And, we make really shitty decisions as a result of our impatience and uncritical consumption of information.

Where we are now, with news reporting, information sharing, mis- and disinformation, demands for instant understanding, and conspiratorial thinking, is not something that has just happened. We have gotten to where we are slowly and in bits. Some things such as the fear of unknowing have been with us since humans assumed consciousness. Conspiratorial thinking has gone on for centuries. Mis- and disinformation is as old as advertising, perhaps going back as far as the beginning of persuasion. The culture of instant is not new.

The struggle with right now thinking might seem to be an acute, immediate danger. It is not. What we are dealing with is a mundane, persistent condition, one which has adapted over many decades to emerging technologies. As such, one of the solutions to our dilemma is also time-tested. It is one which reflects how we used to report and consume the news and other information, a practice that rejects the instantaneous for patience. Not patience for patience sake or for delay, but the patience needed to accumulate information, take it in and understand what we can understand to the best of our abilities, patience which allows for time to tap others for knowledge and understanding when we hit walls or admit that we have no idea what they fuck is going on. The key is to accept not knowing in the pursuit of knowing.

On Wednesday, January 6, 2021, we saw “Trump supporters,†urged by President Trump, storm the Capitol building, vandalize the premises and attack police officers. At the time, few people dealing with the crisis knew exactly what was happening, who – if anyone – was behind the attack, or if the invaders had any plans other than occupying the building.

What was generally known was the event as it was happening and, for many of us, what was being reported in real-time. Police officers being overwhelmed by the mob – in a country with a technologically-advanced, heavily-armed, and situational-aggressive law enforcement institution – told us that there was a failure of some sorts, but exactly what we could only guess. And, yet, though we knew relatively nothing, many flailed to find some dark force responsible for what happened, concocted theories from sparse information and much imagination, and demanded action right now – all panic reactions in a moment of crisis.

Certainly, one must make quick decisions to defend oneself in a crisis, and that is what happened. Congress member retreated and took shelter, while the cops took back the Capitol building. After getting back to the business of presiding over the electoral vote count, Nancy Pelosi contacted the acting Defense Secretary and the Joint Chiefs of Staff to put a firewall between Trump and war. Democrats in Congress pressed Vice President Mike Pence to invoke the 25th Amendment, the only sure way to instantly remove the president, and then set about drafting articles of impeachment, the slowest way, under any circumstance to remove an office holder. House members forced resignations of he head of the Capitol Police, the acting Secretary of DHS, and others. And, then the legislature started investigating what happened.

The alternative to what has been done – reaction for action’s sake – not only can lead to decisions that will haunt us (see the last Soriano’s Comment), but make for a “rush to judgement.†In haste, we scapegoat the easiest catches among the perps – cosplay revolutionists. We haphazardly do a quick mop-up, allowing the major players to escape, while going half-assed on collecting evidence on the “low hanging fruit.†When we get too close to power, we stop investigations for the sake of “national unity.†We allow for space for wrong-doers to receive presidential pardon. We charge into impeachment, which while needed, will not solve the problem of Trump.

The only effective way forward – to a place that brings about both justice and change – is to reframe our relationship with not knowing, to look at the unknown as a necessary start to learning more. Realize that not knowing is not an empty place that must be filled with speculation, gut-feeling, and conspiracy. Bit knowing is a process that allows us time and space to research, investigate, and assemble facts needed to create a fuller story of what happened, a story that serves as a foundation to make the change and get the justice that we need.  ÂÂ

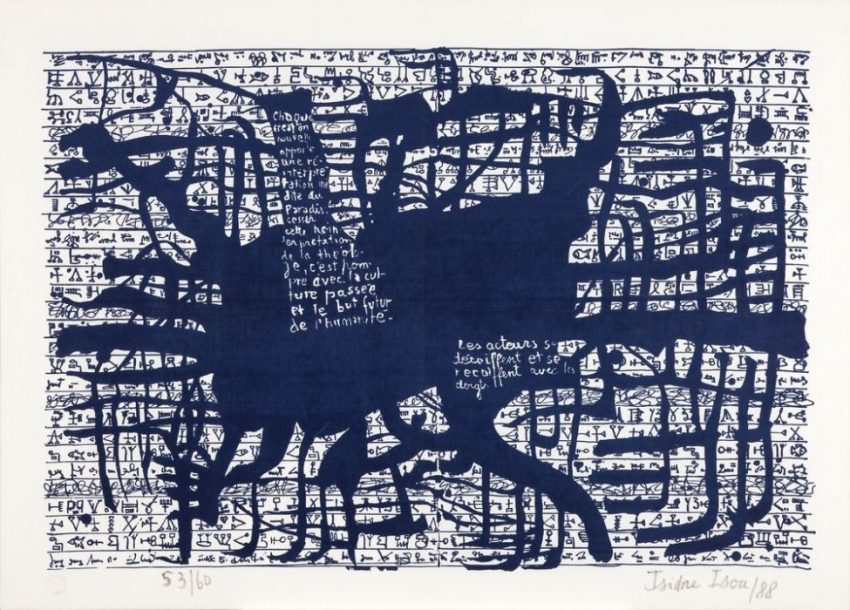

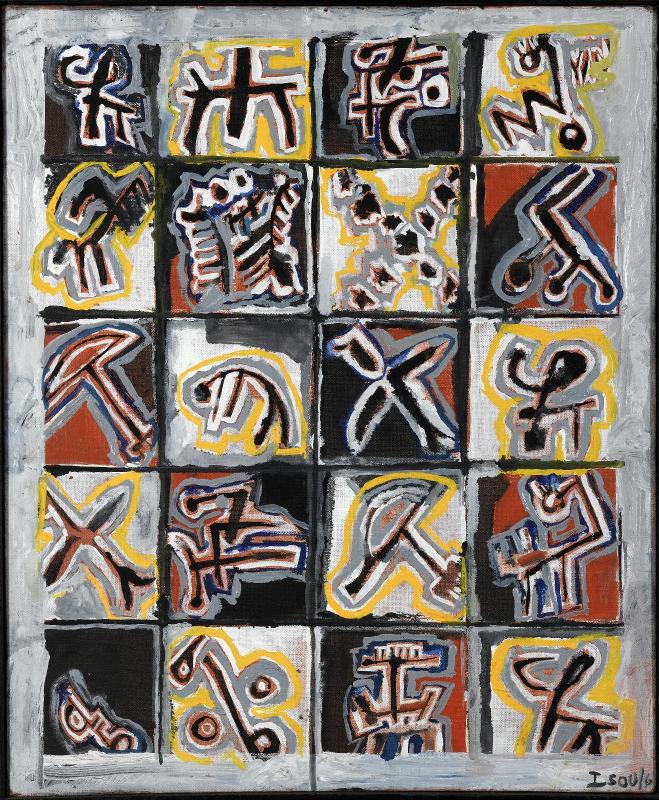

A top: Isidore Isou Polylogue Hypergraph (1964)